Overview: This page outlines the deployment of Japanese teenagers in Mission British Columbia during World War Two and how it affected their lives.

Mission, British Columbia, had a peaceful relationship between the Japanese community and the Settler community, but this all changed during World War Two after the bombing of Pearl Harbour on December 7th, 1941. From that day forward, it was required that

“All Japanese Canadians, regardless of citizenship, were required to register and be fingerprinted with the RCMP; from that point on, no movement from one area to another got permitted without a special permit. A dawn to dusk curfew order requiring them to turn over to a ‘Custodian of Enemy Alien Property’ all radios, field glasses, firearms, [1]

Schroeder, Andreas

Mission, British Columbia, was no exception and promptly announced these measures. [2]

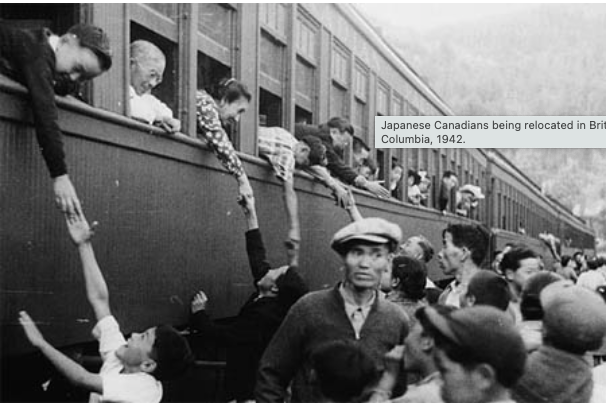

The measures required by the Canadian government affected all the teenagers in British Colombia, and April of 1942 marked the beginning of the evacuation of all Japanese Canadians from coastal regions to re-settlement facilities in the eastern and central parts of the province. With the absence of the Japanese Canadian population in the Mission area, the school enrollment dropped by fifty percent,[3] which was reflective of the high percentage of the Japanese families in the Mission area.

The Japanese Canadians could only take what they could carry with them so they had to leave most of their belongings behind. The officials promised them that they would protect the rest of their belonging. Instead, most of it was lost after the war ended. The Japanese Canadians decided to protest and fight back against this injustice. [3]

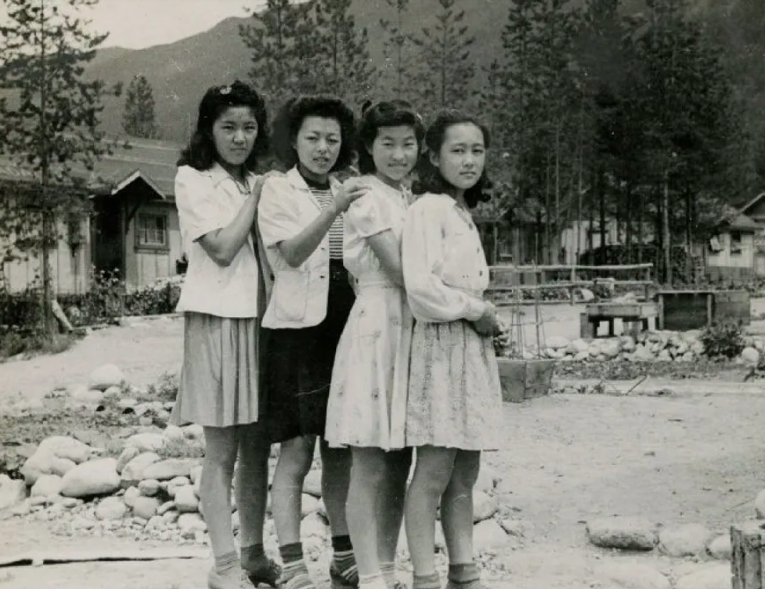

The University of British Colombia Library’s collection of letters written by displaced Japanese teenagers during World War Two, illustrates the struggles they had to endure during this time. We can see a common trend amongst Japanese teenagers during this period in the lives as revealed in their writings. For example, the teenagers expressed boredom at being unable to experience the social life that their white peers were able to experience, as shown in the following letter:

Sept. 24, 1943

Dearest Joan,

Just a sheet with a few lines to say hello and how are you.

It’s been quite a long time since I heard from you last and I hope you are all well as we are also.

I imagine you’re going to school every day and enjoying your everyday life. That’s swell!!!

Life is very dull out here. No school. No play.

Guess what??? It’s beet topping season now. Think of us in the field pulling and topping beets while you’re doing your geometry, social studies, et cetera. Will you Joan? And I’ll think of you having a wonderful time while I work. …

But I have so many things to tell you about the beets and everything out here, I don’t think I could write everything I want to in the letter.

Well, I’m just wishing for the day you and me telling and hearing each other’s stories for hours and hours of what we’ve missed. I only wish it would be soon, don’t you think so Joan?

I’ll write again, a longer letter, and I’ll be waiting for yours every day.

Your friend as ever,

Sumi

Sumi 1943 [5]

We can see the direct impact of the Japanese students’ deployment on the teenage community. They felt lonely and missed out on their adolescent lifestyle.

In Mission, B.C. during the war 100 Japanese families got displaced [7].

When we think about 100 families being from such a small community, we can see the detrimental effects, and how the families got displaced all over.

It got noted that many families moved to

-sugar beet farms in Alberta/Manitoba,

-Dairy Farms

-Interment camps

-Japan (after the war)

-Ontario

-Helping the authorities

-Corn seed farm

-Interior and Northern B.C.[7]

Some families were able to stay as they were employed at the sawmill, so they still need to help. [7]

[1] Schroeder, Andreas. Carved from Wood: Mission, B.C., 1861-1992. Mission Foundation. 1991.

[2] Schroeder, Andreas. Carved from Wood: Mission, B.C., 1861-1992. Mission Foundation. 1991.

[3] Schroeder, Andreas. Carved from Wood: Mission, B.C., 1861-1992. Mission Foundation. 1991.

[4] Landscapes of Injustice. UVIC, https://loi.uvic.ca/narrative/index.html

[5] “Dozens of letters by interned Japanese- Canadian teens donated to UBC.” CBC News, Anna Dirmoff, accessed March 16, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/japanese-canadian-teens-xwwii-1.4632541

[6] “Hide Hyodo Shimizu”

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/hide-hyodo-shimizu

[7] “Japanese Community in Mission: A brief History” Hashizume